Domain Events vs Integration Events

There are different kinds of events found in event-driven systems. They often represent the same thing that has happened, but serve different purposes and have different advantages. Here I’d like to outline the differences between a few terms.

Domain Events

In Domain-Driven Design (DDD), domain events are the things that happen that are of interest to a domain expert. They are written in the ubiquitous language of the domain.

public class SomethingHappenedEvent : IDomainEvent

{

// props

}

These are raised when changes are made to domain aggregates. When domain events are dispatched, their handlers usually make more changes to other aggregates.

internal class SomethingHappenedEventHandler : IDomainEventHandler<SomethingHappenedEvent>

{

// ctor

public async Task Handle(SomethingHappenedEvent domainEvent)

{

var otherAggregate = _otherRepository.Get(domainEvent.SomeProperty);

otherAggregate.DoAnotherThing();

}

}

Transaction Boundary

Whether or not domain events should be handled within the same data transaction is disagreed amongst architects. Some argue that the aggregate is the consistency boundary.

Any rule that spans Aggregates will not be expected to be up-to-date at all times. Through event processing, batch processing, or other update mechanisms, other dependencies can be resolved within some specific time.

– Eric Evans

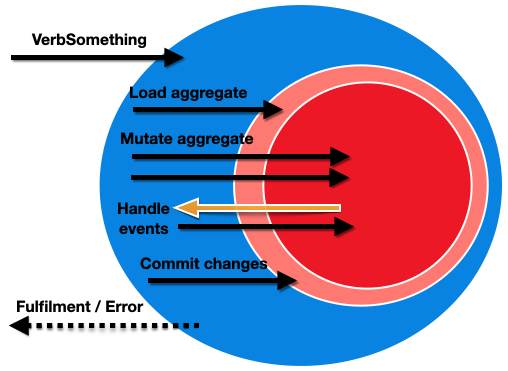

However, Jimmy Bogard proposes dispatching domain events immediately before committing the transaction, so the side-effects of handling the events are all committed together as one unit of work, enforcing immediate consistency. I like this approach myself. It’s simpler to consider one request as one atomic transaction. From the outside, I send my service a request, all the work is done, the transaction is committed, the request has either been fulfilled or there was an error.

Commit Behaviour

When all requests behave this way, it’s easy to define a single behaviour, writing this once and not violating the Single Responsibility Principle.

We can implement our own decorator pattern to ensure that events are dispatched when we commit the unit of work. Or, if we use MediatR to send the requests to our application, we can implement a pipeline behavior.

internal class CommitPipelineBehavior : IPipelineBehavior

{

// ctor

public async Task<TResponse> Handle(TRequest request, CancellationToken cancellationToken, RequestHandlerDelegate<TResponse> next)

{

await next();

await _eventDispatcher.DispatchAll();

await _unitOfWork.Commit();

}

}

In-memory

Events that are dispatched before the transaction do not themselves need to be saved to a database. If they only exist in memory, we don’t need to worry about serializing them, so we’re not restricted on what data they can contain. For example, they could have recursive properties, or maybe even contain sensitive information.

Persisted Events

Committing all state changes within one transaction is not always possible, such as when changing some external state over an API call. What happens if the API responds successfully but then our own transaction fails to commit? We must ensure the state is kept consistent between the two systems.

In this case, we can change our own state first, then ensure the external state change is done after our transaction has been committed.

To do this, Kamil Grzybek proposes dispatching separate domain event notifications after the commit. This is a nice distinction and gives us the choice to handle inside or outside the transaction by handling the domain event or the domain event notification.

Because our database transaction has already been committed, we will need to ensure the notification is processed even if the handler fails or our application crashes, otherwise our system could be left in an inconsistent state. We can implement an Outbox pattern, which writes the notification to a data table as part of the same transaction and processes it later.

One way of achieving this is by implementing a generic domain event handler for all domain events.

internal class DomainEventNotificationOutboxHandler<TEvent> : IDomainEventHandler<TEvent>

where TEvent : IDomainEvent

{

// ctor

public async Task Handle(TEvent domainEvent)

{

_outbox.AddNotification(domainEvent);

}

}

A separate background process would dispatch events from this outbox to the notification handlers. Exceptions in these handlers will not cancel the original transaction because it has already been committed — the event has already happened. We will need a retry policy if these handlers fail. If they continuously fail, we must raise an alert for a human to deal with the problem.

Eventual Consistency

The original request to commit the first transaction would return to the client before the above notification is processed. From the client’s point of view, their request was successful and all their changes will be reflected in the rest of the system, but maybe not immediately. The state changes will be propagated eventually through the handling of these notifications.

Integration Events

That all sounds like a similar concept to the integration events defined in Microsoft’s .NET Microservices Architecture e-book:

The purpose of integration events is to propagate committed transactions and updates to additional subsystems, whether they are other microservices, Bounded Contexts or even external applications. Hence, they should occur only if the entity is successfully persisted.

The difference is that the types of events mentioned earlier would be handled internally within the boundary of the domain, whereas integration events are part of the public API contracts that other systems can subscribe to.

These could be published to subscribers using an Event Bus like RabbitMq, or some HTTP callback method like WebHooks or SignalR.

Because they are public, they must be versioned somehow. We can’t make breaking changes to events that external systems are subscribed to. This could be achieved similarly to other public APIs by maintaining multiple versions of the same event until all clients have migrated.

Query the Event Store

Rather than publishing the events, another option is to allow clients to query them. We would need to persist each event to some storage.

internal class EventStoreHandler<TEvent> : IDomainEventHandler<TEvent>

where TEvent : IDomainEvent

{

// ctor

public async Task Handle(TEvent domainEvent)

{

_eventStore.AddEvent(domainEvent);

}

}

This could be the same persistence used for the persisted events mentioned earlier. Rather than removing them from the store once they are handled, they could remain in an event store for a period of time. This gives clients the option to query for events they may have missed or lost somehow.

Event Sourcing

In fact, an event store could even be the primary source of the domain’s data. We could rebuild the state of aggregates just by applying these events, then we wouldn’t need a transaction to persist them atomically with the state changes — they are the state changes.

Or we could do that and still use a transaction to persist the event along with a change to a separate read store. But we are now delving into what should perhaps be a separate post about CQRS…